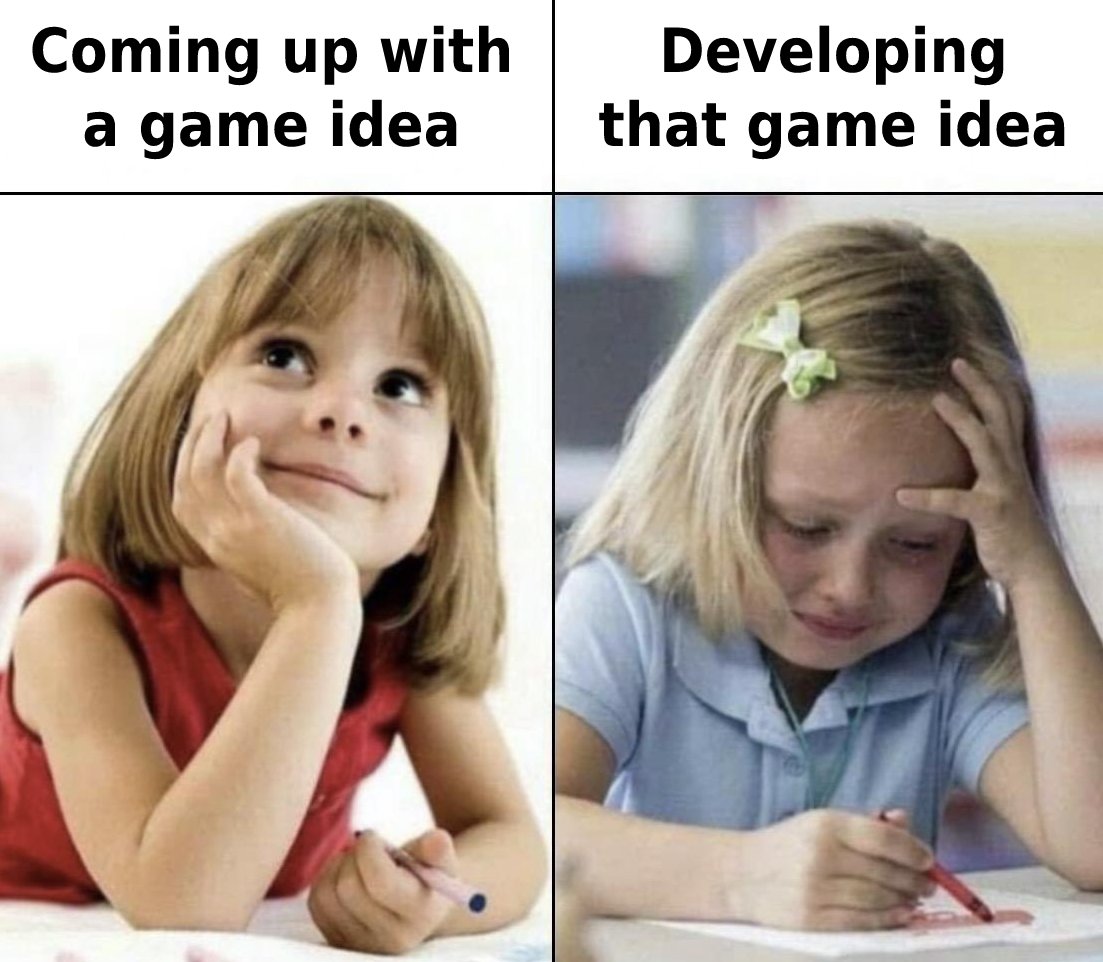

The iPhone App Store had just been revealed. Gamers and players were both flocking to it, hungry for apps and especially games to play on their new devices. It was the perfect opportunity to try a new game idea I had been imagining for a while.

I sat down to start writing code and painting sprites, and in a few weeks I had a playable game that looked great on the new phones. It ran smoothly, and even looked pretty good! But there was a problem…

It just wasn’t fun.

I started tweaking the controls, improving the art, and adding features - but nothing seemed to make it fun to play.

Finally, after wasting weeks trying to make the game work, the realization dawned on me: I had not made a “game”, I had made an “activity”. No amount of polishing was going to fix the problem, it would need entirely different gameplay if I was going to save it.

Game vs Activity: What’s the Difference?

As game designers, we need to understand the fundamentals of the games we’re trying to build. Lets start with the dictionary definition of Activity:

the quality or state of being active : behavior or actions of a particular kind

So, an activity is basically just “doing stuff”. In my game, the player had to do stuff in order to progress, so what’s the problem?

Well, the same definition fits taking out the garbage, writing an essay for english class, or flossing your teeth. None of these are a game, so how do we get from one to the other?

The next obvious step is to add some missing pieces that any game should have, like:

- Games have a goal

- Games have rules

- A game can be won or lost

This is an improvement, but it still can’t be the whole story, right? Our definition so far also applies to an election, or a raffle, and those aren’t really games.

My iPhone app had all these peices as well. It had a goal (escape to the next level). It had rules (a limited set of actions), and it could be won or lost. It seemed to meet all the criteria to be a game, and yet it didnt feel like one. Clearly something is still lacking from our definition so far.

Here’s a game example that fits - and even adds in animations, sound effects, and epic music:

While this almost feels like a game, and admittedly is similar to some existing “games”, it’s not fun and I don’t think anyone would play it on purpose.

How do we make it fun?

The primary reason it isn’t fun is that there is no challenge. A fundamental part of playing a game is meeting a challenge, figuring out how to solve some problem, or making interesting decisions.

Jesse Schell has an elegant definition of a game in his book “The Art of Game Design”

A game is a problem-solving activity, approached with a playful attitude.

People are wired to enjoy solving problems, and this is where a large part of the “fun” comes from when playing a game. If we think about the different genres of video games, this holds true about most of them:

- Puzzle: Solve each puzzle presented

- Platforming / Jumper: Discover and follow the optimal route through a level without falling or losing to traps or enemies

- Racing: Find an maintain the optimal line through the course

- Fighters: Learn to predict and counter your opponents attacks, while landing your own

- FPS: Discover moving & shooting tactics that work for the current environment and context

As the game progresses, the challenges typically build upon one another to get more and more difficult. At the same time, the player is learning and applying new skills to each challenge. This is the feedback look that forms a “hook”, pulling players into the game and making them want to continue.

Maintaining an appropriate level of challenge through your game is an important skill for every game designer. Challenges that are obvious, and don’t allow the player to learn or improve will fail to draw the player in. Challenges that are too hard will feel unfair, breaking the feedback loop, making the player want to quit.

Applying to our own games

We should always be thinking about the different ways of challenging our players, tuning the difficulty, and examining our games through this frame. Consider what problems we are aksing them to solve, and what interesting decisions we’re requiring them to make.

The best time to start is as soon as you begin your design, but it’s never too late to start, and it’s worth keeping in mind throughout a game’s development.

In future posts we’ll examine other ways to think about and maybe improve our own game designs.